Reviews

Reflections

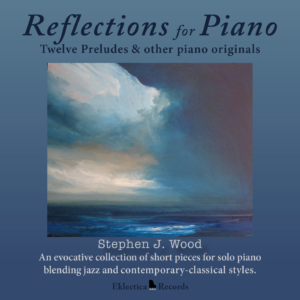

Twelve Preludes and other piano originals by Stephen Wood

There is something beguiling about Stephen Wood’s writing. The twelve Preludes mirroring, if in title alone, Tchaikovsky’s Seasons, are named after each month of the year and provide an enticing, intriguing and attractive addition to the piano repertoire. Aimed, I sense, at the teenage pianist (or perhaps also the more sentimental adult) they are effectively a set of improvisations, each with their own mood and personality, followed by a ‘coda’ of two pieces, the short, reflective ‘Stella‘ taking the performer into the cold night sky and finally the more substantial musical narrative of ‘Another Time…‘

It’s the harmonic language that makes these pieces stand out from the crowd; some luscious jazz harmonies mingle with a more chromatic and contemporary approach. They are rarely predictable yet have a natural and instinctive ebb and flow, often providing a rewarding canvas of sonority and repetition upon which to convey a performer’s own personality, thoughts and ideas. If you want a strong taste of the contrasts in these pieces compare the bitter, chromatic and acerbic September with the entrancing warmth of the wistful waltz in May.

My favourites include the evocative January, its strong improvisatory approach and sumptuous harmonies

Small hands may struggle to play a few of the pieces, there are some quite significant stretches and I feel the shorter Preludes are generally more successful and convincing. I loved the opening of March for instance but the middle section and return felt just a little too long and drawn out for the musical ideas, but then again I’m very much one for ‘concise and distilled’.

All the pieces respond to an instinctively musical approach and will engage the imagination of any performer who has a love of harmonic shifts and surprises, a natural sense of rubato and a good control of balance and voicing.

Sincerely felt and rewarding compositions such as these can’t fail to motivate and inspire.

Articles

‘but it’s only Grade 1 …’ – May 2018

The advent of a vibrant, exciting new ABRSM syllabus promises a rich seam of carefully graded, imaginative and inspirational pieces. The graded repertoire is a fabulous resource perhaps not so often exploited as it might be; indeed over the past 20 years alone well over 1700 pieces have been sensitively and carefully chosen to provide the most motivational and characterful repertoire possible to use within an assessment framework. These pieces are also selected by experienced teachers who themselves are, and will be, using the repertoire to engage young children through their early piano years. For the new syllabus consultation with specialist teachers has been wider than ever before.

The level of challenge presented at each grade is historical. We are all aware that there is a lot of musical and technical ground to cover to reach Grade 1 on the piano and an impatience to take the first grade may be one of the main reasons that many early grade performances whether in exams, schools or festivals are more of an exercise in perseverance rather than a musical experience. Delightful, colourful and evocative pieces are sometimes reduced to a means to a graded end, possibly driven by parental pride, and the ability to get fluently from the start to the finish of a Grade 1 piece is then interpreted as the surest sign that Grade 2 must be on the horizon. The sadness is that this wonderful repertoire is not then being used as a vehicle for encouraging the performer’s own musical thoughts, nurturing the musical ambition or developing the more subtle awareness and control needed for the future.

I thought it would be interesting to take a cursory glance at the new ABRSM syllabus and, starting from Grade 8, discover a ‘backwards pathway’ through a few highlights which might illustrate the value of waiting until the right moment to take an earlier grade, ideally the point at which we can work with the pupil not just towards an accurate rendition but a musically persuasive performance. Amidst the pressures placed by parents, schools and indeed the pupils themselves to take the next exam, we need to be advocates of what I call an appropriate ‘level of challenge’. It’s the point in their development where the amount of the time we (and they) spend in a lesson on learning to get from point A to point B in a new piece would be no more and preferably significantly less than the time spent working at interpretation and expressive playing.

A quick glance at Grade 8 reveals the second appearance of the truly gorgeous Rachmaninoff Elegie to use as an example. Its dark, passionate opening relies on a strong, shapely projection of the melodic line and a really keen ear for, and control of balance. The left hand arpeggio figures have to be fluent but also gently and quietly shaded to the top to avoid interfering with the sustained yet decaying longer melody notes. The middle section with its more optimistic cello-like melody requires even finer control of balance. The softest of right hand chords are needed to allow this tune sufficient dynamic space to eloquently express its heart-felt character. The return of the melody in 6ths requires a subtle and consistent control of balance within one hand, and throughout the piece the legato pedal needs refined control at the point of lift of the dampers and above all the most astute listening to the speed and timing of the pedal changes.

At Grade 5, making its first appearance into a recent syllabus, is the haunting and beautiful first Vision Fugitive of Prokofiev. It stands as one of my favourite teaching pieces, containing so much musical intensity and imagination in a few bars that it is easy to capture the imagination of most pupils. Unsurprisingly, a convincing musical performance challenges many of the areas that the Grade 8 Rachmaninoff demands yet within the context of simpler textural challenges. The melancholy mood of the opening is conveyed by a shapely melody and, crucially, a well controlled and engaging balance between hands but it is in the return of the tune that balance is challenged to its utmost. The ‘teardrop rolling down the cheek’ image of the chromatic line requires the top line to sing intensely yet quietly over the top of the delicate, descending scale and chords, all within one hand. The pedal also needs to be finely judged, held just at the point before the dampers lift, its movement small and influenced as much by the sound as the changing harmonies.

At Grade 3 and below we can see how, often within a single piece, the repertoire focusses on and encourages a single element of the technical control of sound needed for the Rachmaninoff. The wonderful Walter Carroll makes another welcome appearance. Long neglected as an ‘old fashioned’ composer and now rightly firmly back in the syllabus over recent years, Carroll’s Shadows is relatively unsophisticated in its musical imagery but in order to convey and communicate the mood of changing shadows and warm sunshine, a really good ear and timing of the pedal are needed. It is not too early to introduce young pianists to the idea of the damper pedal not being a switch but a colouring tool, working from the point of damper lift rather than the extremes of the movement.

Lazy Bear by Neugasimov in Grade 2 gives the pupil a chance to explore projecting a bold left hand melody without having to worry about the finer musical subtlety needed for the Rachmaninoff when encountering the same technical challenge. Lots of variation in the weight behind the left hand fingers will shape and breathe life into the growling legato phrases and begin to develop the strong musical shaping needed for later grades, and by coupling this with lightly placed (and not too short) right hand chords the image is quickly brought to life.

At Grade 1 the notes are far less demanding technically and texturally of course but nevertheless expressive playing is paramount. Many of the seeds of sound needed for the Rachmaninoff are sown at this point. The truly delightful and dreamy Head in the Clouds by Andrew Eales requires an intense awareness and control of balance between the hands, containing as it does, like the Rachmaninoff, left hand and right hand melodies both needing and expressive dynamic shape and independence to nurture the ‘deep in thought’ nature of the piece. It goes without saying that if the level of challenge is simply learning the notes then there is the strong risk this emotional engagement might be absent in an effort to acquire fluency. There may only be one bar of pedal marked but developing an aural awareness of the opening left hand held notes and their release is part of the listening skills needed for good pedalling.

In the same grade the enchanting Brahms Wiegenlied arranged by Nancy Litten needs an awareness of balance between a decaying melody note and left hand accompaniment to carry the vocal melody to the next note. This is significant. Unnoticed, the listening awareness and control needed to hear and adjust the left hand arpeggio figures in the Rachmaninoff may be under-developed.

These early grade pieces are, in essence, laying the musical foundation stones for the intense musical and technical challenges of the Rachmaninoff at Grade 8. Anything short of encouraging and inspiring a convincing musical performance of the early grade pieces may mean we end up later on with pupils who are solely practitioners, at best unable to convey their musicianship, at worst not musicians at all.

With a new syllabus of inspirational and motivational pieces to learn for an ABRSM assessment, it is worth considering for each pupil how long you are likely to spend with the building blocks of accuracy of notes and rhythm and how much time nurturing the tonal control and awareness, expressive shape and colour and musical communication. If these are out of balance then consider whether the musical message to the pupil (and, more likely dare I say it, to the ambitious parent) is strong enough or, more likely, whether the repertoire and grade level is too hard.

If a pupil does not demonstrate musical engagement, expressive communication and control, what messages do graded exams send out? How disappointed will our enthusiastic musicians be when they can’t do immediate justice to later repertoire as there are so many musical holes to fill? How sad would it be if the thought and care that has gone behind the new syllabus choices to motivate and inspire our young musicians is cast to one side in a more practical effort to get from the beginning to the end?

We should always believe that performance of a Grade 1 piece can and should be as subtle and musical as later graded pieces, and it’s in the interest of our future pianists and musicians that we dispel the myth that anything less is acceptable because ‘it’s only Grade 1’.

‘The technique of a musical performance’

Here’s a little experiment.

Listen to your pupil play, whether it’s a few notes or a whole piece, and make a mental note of the very first thing that you say or want to comment on. Is it the wonderful balance between the hands on the third beat? The subtle shading at the end of one of the phrases? The expressive nuance or placing of a specific note? The awareness of the mood or atmosphere? Or was it the technical unevenness of a passage, the wrong note in bar 4, the rhythm in the third line or the fact that the pupil hasn’t learnt as much as you had asked for? What message about the performance will you convey to your pupil by your first response?

Whilst any moment of musical persuasiveness or communication may have been accidental, perhaps even one note only, did you, as the teacher, notice it and give it its due importance or did you relegate it to the background whilst dealing with inaccuracy or technical issues? It is an important question because it is in these moments that musical performances are encouraged and inspired.

It may well take several years for a pupil to reach a more advanced level and during that time there will be a lot of conditioning by the teacher and consolidation by the pupil, but of what? If our first reaction to a piece is to point out a wrong note or rhythm then we are conditioning the pupil into believing that accuracy is the overriding priority in their playing and, more significantly, they may then dwell on this when they come to a public or exam performance.

Musical aspirations, awareness of performance and the subtle art of communication shouldn’t ever be last-minute pre-performance ‘bolt on’ extras once the notes have been learnt. The inspiration, imagination and emotional connection with music needs to be ‘drawn out’ of a young musician over years, building on just those very occasional moments where they have happened naturally or even accidentally.

The nurturing of a musical performance therefore begins with the first note a pupil ever plays of any piece, whether it is Grade 8 or ‘middle C’ in their first lesson. The musical instincts and expectations of a young musician must be allowed to grow by focussing on those occasional glimpses of what is musically possible. Praising pupils for one small moment of magic and questioning them about how they produced it or might produce a particular sound or shape to a phrase again will inspire and persuade them to explore using similar sounds or ideas elsewhere in the piece.

But, you might think, don’t control, technique and accuracy have to come first? I would suggest exactly the opposite. If enthused and motivated to produce a particular sound, whether it is ‘raindrops and thunder’ pre Grade 1 or a true cantabile or beautiful balance between hands later on, most pupils will be inspired to repeat phrases and passages until they discover the way to control it. The learning of the notes will happen incidentally; the repetition needed for fluency fuelled by a personal connection with the music and sound. What’s more, the very fine motor control and technique needed for the interpretation will be reinforced from the first note rather than having to be re-learnt with the right touch.

If piano lessons are focused upon the sound, interpretation, imagination and communication behind the music then you will hopefully have motivated them to work towards the control they aspire to and they will put in the hours of their own volition. If you have instilled in your pupil from the earliest stages that music is all about character, sound, colour and a personal voice then they will naturally turn to playing (and practising) as an outlet for their emotions. Playing the piano will be something that is as important to their well-being as the next meal. Within the context of encouraging a beautiful, seductive whisper, a moment of content, a song-like shapely melody you can of course mention technical unevenness or a wrong note but hopefully without dampening their enthusiasm. A simple ‘by the way, that’s an Eb’ will suffice and be something they aspire to get right part of an inspirational and creative musical end.

So be brave. Experiment and make the starting point of every lesson the interpretation and sound produced, even if only three notes have been learnt; challenge yourself to reflect on every positive and convincing musical moment before turning to inevitable corrections and technical advice. If you put the character, sound-world and personality of the piece at the heart of every lesson you may well be surprised at the technical polish and control this inspires from the pupil. It will not be long before you will find yourself listening not just to a pianist who can play the notes but a genuine musician who brings their personality to a musical performance in a personal way, inspired to practise and relate to music not just as a practitioner but as a convincing, expressive, communicative pianist.